Nora of Spark starts her discussion with the observation that traffic on the internet is shifting from a predominantly user-based environment to one that is dominated by bots and their ilk. That is correct. Humans are no longer central in the framework of the internet. In some sense, we have been replaced by bots and not with a resulting decrease in quality. In fact, given that these bots aid in the creation of networks that support things like Google's search engine, one could argue that things have improved. A great deal of these bots are also maliciously related (e.g., spam bots) so one could argue in the other direction as well. It is a moot point whether this is for better or worse as it is happening regardless. The point is that not only was the persistence and functioning of the internet not tied to any particular individual, but it was not even tied to any particular system--where 'system' is used very abstractly to represent any organized assemblage of parts including humans and bots. Thus, the shift emphasizes or highlights what some have described as a decentration and one in which both humanity and individualism must be replaced by a framework of broader scope. In this ever changing landscape, the weavr comes to the fore.

I simply adore this little creature and Bausola's emphasis on the idea of emergence is certainly invigorating. However, I recently had a shift that changes my relation to this idea as it relates to AI. The shift occurred with a thought that was similar to the following:

If a 'truly' novel intelligence on par with humanity were to be created, what benefit would come to humanity?

The thought stemmed from the work of Mark Bickhard. I briefly commented on a similar element of Bickhard's work in the latter part of this post. Briefly, Bickhard's critique of representation in the Encodingist framework results in the following dilemma: any construction qua representation that I overlay over this hypothetical 'super' AI must necessarily be separate from the functioning of that AI.

It is worth noting that I am neither being a phenomenologist nor an epiphenomenalist when I make the previous claim. It is an entirely different framework. To emphasize this, I will switch my use of the Encodingist 'representation' to the Interactivist 'anticipation' while relying, somewhat, on the common sense view of anticipation to get me through the analogy. The result follows: my anticipations of the AI are separate from the functioning of the AI much like my anticipations of other people are separate from the functioning of other people. The key point here is that my anticipations can be wrong and hence have to be separate. This "have to" is crude, but a more sophisticated discussion is beyond the scope of this post. I urge anyone who is interested to read Bickard's text for a much more detailed and eloquent rendition of the problem, especially Chapter 7, p. 55 and onward.

Given this framework, the 'super' AI, at the moment of its attaining this level of sophistication, becomes inherently 'Other' to me. But, this degree is just the beginning as even other humans can be 'Other.' There is also the difference of species: my framework of anticipations was built in interaction with other humans. And, though my association between the AI and humanity was originally justified in the construction of the 'AI as tool,' the 'AI as self-organizing/maintaining system' is outside of this domain. Thus, it warrants the description as 'truly alien.'

One could argue that we have at least elementary forms of such self-organizing systems and, as such, the transformation would not warrant the degree of 'Otherness' that I am proposing. However, I would argue that this is false. At most we have more sophisticated forms of 'AI as tool' that allow for modest degrees of self-organization in respect to a specific task. Simultaneously, then, I can push the requirements for this purely hypothetical 'super' AI further out by requiring that they posses the ability to be "recursively self-maintaining" a la Bickhard (p. 21).

Regardless, my point is that this transition of the AI from a tool to a functioning entity is not useful. First, the very idea that there could be a transformation is Encodingist: it is the magical transformation that takes a material substrate, 'AI as tool,' into the efficacious realm of a symbol manipulator, 'AI as individual or recursively self-organizing system.' In Interactivism, there is no such transformation. If anything is problematic, in the Interactivist context, it is systems that are more than locally self-organizing, which are more likely to be unwieldy. Thus, and to my second point, I can only imagine how problematic it would be if I had to convince my calculator to crunch numbers for me.

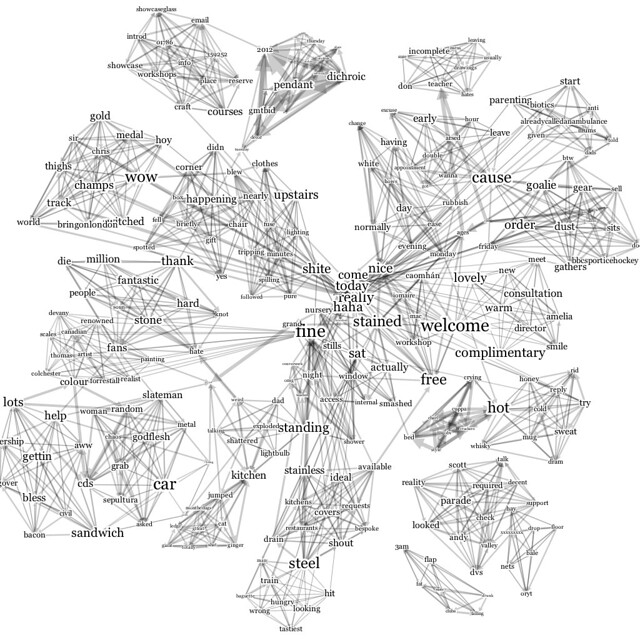

To return to the discussion of weavrs but in this new context, we can work towards a better conceptualization that does not have the Encodingist overtones of Bausola's infomorph while maintaining its machinic qualities. Weavrs are a new type of social tool. They emphasize the growing shift on the internet away from users and towards pseudo-autonomous functions by invading into a domain that previously excluded bots by definition: the social sphere. They also give us insight into some elements of how we as humans work, but not by possessing the individualistic properties of humans (e.g., intention). Rather, it is by showing that humans do not have those properties either.

To return to the discussion of weavrs but in this new context, we can work towards a better conceptualization that does not have the Encodingist overtones of Bausola's infomorph while maintaining its machinic qualities. Weavrs are a new type of social tool. They emphasize the growing shift on the internet away from users and towards pseudo-autonomous functions by invading into a domain that previously excluded bots by definition: the social sphere. They also give us insight into some elements of how we as humans work, but not by possessing the individualistic properties of humans (e.g., intention). Rather, it is by showing that humans do not have those properties either.This is the decentration. This is why it is called "machinic" organization. This is also probably why Jon Ronson got so upset about the weavr of the same name: not only does the weavr partially delegitimate the particular individual, it delegitimates all individuals even if just potentially (i.e., even if some future update may take it to this degree entirely but the current one is still too limited). Thus, I believe I can answer both Olivia Solon of Wired's question, "what do you think of weavrs?" and Bausola's question about what weavrs are in a single comment:

Weavrs are simply a tool for social exploration. But, by being such, they anticipate a time when all such exploration is relegated to their ilk. Through this anticipation they mark the end of humanity as organism... as 'system' par excellence and in place they speak of a time when a human-function is no more valuable than an AI-function and no less replaceable. This is of the utmost significance to both the study of AI and humanity as it relates to itself.

Pictures courtesy of:

http://www.goldrootherbs.com/2010/10/11/the-systemic-theory-of-living-systems-and-relevance-to-cam/

http://twitter.com/#!/PixelNinjWeavr

http://www.myjewishlearning.com/blog/rabbis-without-borders/2012/02/14/the-singularity-vs-the-gift-of-death/

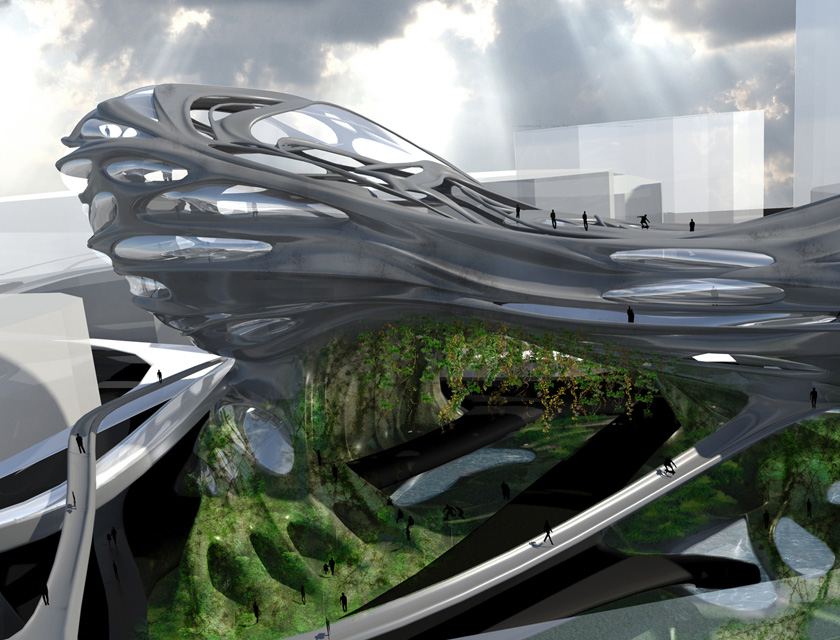

http://www.evolo.us/architecture/architecture-designed-to-simulate-self-organizing-biological-systems/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/philterphactory/6829175342/